Carlsberg, the Danish brewer, opened its seventh brewery in India two years ago: a $25m plant, capable of brewing 50m litres a year of beer, in Bihar — a state of nearly 100m. Alcohol demand was growing in the state and the brewery was mostly intended to sate local drinkers’ thirst. But on April 5, the Carlsberg plant, like all the breweries and distilleries in Bihar, was ordered to halt production and shipment of its brews.

Carlsberg, the Danish brewer, opened its seventh brewery in India two years ago: a $25m plant, capable of brewing 50m litres a year of beer, in Bihar — a state of nearly 100m. Alcohol demand was growing in the state and the brewery was mostly intended to sate local drinkers’ thirst. But on April 5, the Carlsberg plant, like all the breweries and distilleries in Bihar, was ordered to halt production and shipment of its brews.

Without warning, Nitish Kumar, Bihar’s chief minister, had imposed prohibition on the state — an election victory gesture to poor women angry at the level of alcoholism in their communities. Tax officials stationed at the Carlsberg plant to count every bottle of beer shipped out — and collect excise duties — were transformed overnight into prohibition enforcers.

“We were all shocked; nobody was expecting it,” says a brewery employee, who asked not to be identified. “They said, ‘If you don’t stop production, sales and dispatch immediately, you are liable for 10 years in prison’.”

The plant has been idled ever since. Nearly 2,000 workers once directly or indirectly involved in making and shipping beer are gone; just a clutch of staff turn up each day. “We cut the grass and maintain the factory and equipment,” the employee says. “But we don’t know how long we can come here, sit and not do anything.”

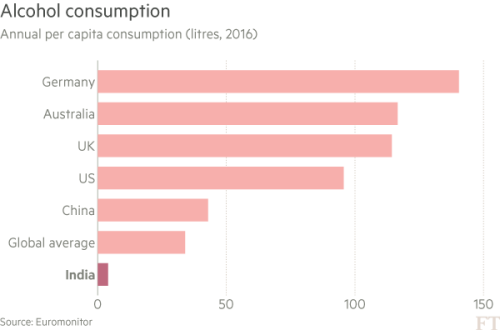

The languishing brewery is an appropriate symbol for India’s alcoholic beverage market. Although sales are estimated by Euromonitor to hit $39bn this year, the country of 1.2bn people remains one of the world’s most untapped markets. In the past decade, multinationals like Diageo, Pernod Ricard, SABMiller, Heineken and Carlsberg have all bet on growth in India, given its young population, rising incomes, changing attitudes towards alcohol and taste for western spirits and beers. Per capita consumption, at 4 litres a year, is a fraction of that in the west and many other emerging Asian economies, suggesting there is plenty of room to grow.

“When we look at different parts of the world, India really stands out in terms of the growth numbers projected,” says Abanti Sankaranarayanan, head of corporate relations at United Spirits, India’s largest spirits company, formerly run by tycoon Vijay Mallya, which Diageo recently paid £1.8bn to buy. “It is a less penetrated market for alcohol, and it’s a market very attuned to what we call western-style drinks.”

‘A necessary evil’

In a notoriously difficult country for business, the drinks industry faces special hurdles. India’s states each have their own regulatory controls on the production, marketing and distribution, and even pricing of alcohol. United Spirits, for example, says it needs 200,000 permissions, licences and approvals a year to operate its business. The red tape reflects India’s dual policy objectives of discouraging drinking — as enshrined in the constitution — while simultaneously trying to extract the maximum revenues for public coffers, and, sometimes, private ones too.

“Liquor is a complicated and difficult subject,” says industry veteran Deepak Roy, executive vice-chairman of Allied Blenders & Distillers, India’s largest domestic spirits company by volume. “They realise it is a necessary evil and you cannot do away with it but they make it difficult for people to operate.”

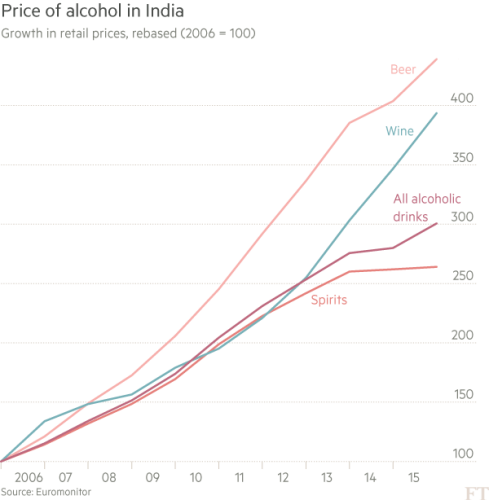

Drinks makers once enjoyed double-digit growth in sales as consolation for dealing with the maddening red tape. Yet that has evaporated in recent years. Rising consumer prices have pressured sales growth, which has been below 2 per cent for the past two years. Margins are shrinking too.

Last year, SABMiller, which sells about 25 per cent of the country’s beer, took a $313m writedown on its Indian investments, citing a reduction in its medium-term growth expectations. Companies could face more disruption.

Mr Kumar, who has national political ambitions, is taking his prohibition campaign to other states, where he has a receptive audience among rural women and social activists, with many demanding a fresh crackdown on booze.

India’s official antagonism towards alcohol is a legacy of its revered independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, a teetotaller who viewed drinking as a major social evil and campaigned vigorously against it. His influence led to Article 47 of India’s constitution, which commits the government “to endeavour to bring about prohibition” of alcoholic beverages as one of its “primary duties”.

For the first few decades after independence, New Delhi pushed for prohibition and in 1977 Morarji Desai, the then prime minister, vowed to usher it in within four years. The effort stumbled, though: alcohol sales were a critical source of revenue for states, and they refused to ban it outright.

But drinking was stigmatised. Those who drank — mostly men — did so covertly, away from home. Bollywood films of the 1970s usually had at least one character succumbing to the temptations of alcohol and destroying themselves as a result. India’s few urban middle-class public bars — outside five-star hotels or private clubs — were dark retreats, whose grim ambience conveyed that drinking was far from a legitimate activity.

“If anybody was drinking, he was considered to be a drunkard and somebody shunned by society,” says Mr Roy. “It became a very surreptitious activity.”

Dependency issues

That changed with Bangalore’s 1990s-era “brew pubs”, which blasted loud music and catered to a young tech industry crowd. Initially, they were such a novelty that well-off youth from across India made pilgrimages to experience them. Today, attitudes towards alcohol have changed dramatically, especially among the young, affluent city-dwellers, and bars exist in many cities.

“Alcohol has come out from the closet,” says Dheeraj Sinha, chief strategy officer in South Asia for Leo Burnett, the advertising agency. “It has become part of the new urban lifestyle, which says indulgence is OK. Alcohol is something that helps you open up — not as something devilish that will take control of you and destroy you. The whole conversation around alcohol has changed.”

That change has yet to percolate throughout society. In poorer, traditional communities, especially slums in rural areas, alcohol is viewed with suspicion as something consumed by degenerates, and that contributes to poverty and violence against women. That helps justify the repressive policy environment. Industry executives say their sales remain stymied by a combination of exorbitant taxes and stifling state controls on the sale of alcohol, ostensibly aimed at limiting consumption.

“The big problem we have is that it’s not a level playing field,” says Lord Bilimoria, the Indian-born founder of Cobra Beer. “Each state has its own excise rules and regulations and taxes.”

In fact, Indian states are highly dependent on alcohol taxes, which can account for as much as a quarter of their revenues. On average, industry executives say, 60 to 65 per cent of the consumer price of spirits is taken up by government taxes, which have been rising sharply, even as states refuse to let companies raise their pre-tax prices. Taxes on imported spirits are 150 per cent.

“The consumer price of liquor is very high because of taxation — not because the manufacturers are walking away with it,” says Ms Sankaranarayanan.

Tax relief will not happen any time soon. Alcohol was excluded from India’s new national goods and services tax, which is creating a single market, and national tax structure for most other goods. Instead, beer and spirits will continue to face state-level taxes and duties at far higher levels than other products.

The fragmented tax structure leads to other inefficiencies, as most states impose high “import” duties on alcohol made in other parts of the country. Manufacturers are thus forced to operate small plants to serve every state instead of a handful of bigger ones serving larger regions, making logistics and quality control difficult. “You have to produce in every state because there are huge penalties for taking stock from one state to the other,” Mr Roy says.

In many states, companies owned by regional governments have roles as distributors or retailers, allowing them to collect an additional 15 to 18 per cent of the consumer price. Often these state companies act as gatekeepers to control manufacturers’ market access and pick favourites, which may reflect politicians’ financial ties to specific companies, rather than local demand.

“It has become a huge political patronage system,” says Mr Roy. “Some of the multinational companies coming into this country are finding it extremely difficult to operate.”

Politically profitable

In Uttarakhand, multinationals including United Spirits and Pernod Ricard took the government to court last year, after it set up a state alcohol distribution agency. The companies claimed that officials refused to place orders for popular brands even as retailers were clamouring to restock empty shelves. The manufacturers were barred from supplying retailers directly, leaving them at the mercy of the state agency. The court ruled in the multinationals’ favour, saying officials had acted arbitrarily and in a discriminatory manner but nine months of sales were lost.

“It is a highly politicised, opaque market,” says James Owen, senior partner for India and South Asia at Control Risks, a global risk consultancy. “There are significant problems in the supply chain, mostly related to bureaucratic and corruption-related challenges. There is pressure from low to mid-level officials trying to supplement their income by requiring payments to expedite permit approvals. It’s a headache.”

Other challenges include the national ban on alcohol advertising, which makes it difficult for companies to raise awareness of new products, and widespread counterfeiting of upmarket brands by criminal gangs, who steal empty bottles and refill them with low-grade hooch.

Yet it is the proclivity of politicians to woo female voters with promises to restrict, or prohibit, alcohol sales that arguably poses the greatest threat of disruption to the industry. In 2014, Kerala, one of India’s biggest drinks consuming states, unveiled plans to go dry over the next decade. It began by banning the sale of booze in all hotels and restaurants aside from the five-star variety. Now, however, Bihar’s draconian prohibition makes Kerala look progressive.

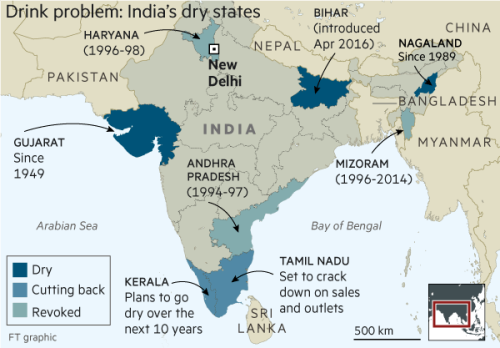

Industry veterans remain sanguine, insisting prohibition does not pose a long-term threat. In the 1990s, Haryana and Andhra Pradesh both imposed prohibition — only to reintroduce booze within two years, amid acute financial crises. Only Gujarat, Gandhi’s home state, has managed to maintain prohibition for decades. But cheap illegal liquor, often spiked with chemicals to make it more potent, remains easily available in these locations, with sometimes deadly consequences. Many in the industry are betting that it is only a matter of time before Kerala and Bihar, which has already faced legal challenges over the severity of the punishments laid out in its prohibition law, give up too.

“I’ve seen prohibitions come and go, and this political adventurism only lasts for a year or two,” says Mr Roy. “In this industry, you have got to learn to live with it. They are a temporary setback but sales pick up in the adjoining areas.

“In the long term, I’m very optimistic. Drinking is part of the social milieu now. If you want to open anything — a personal relationship or a business — everything is done over a drink.”

Local spirits: A cocktail of options serving different markets

Indians may not drink as much as people in other parts of the world, and a large portion of the population, including Narendra Modi, the prime minister, are teetotallers, like one of the country’s founding fathers, Mahatma Gandhi. But Indians have a complex alcoholic drinks market and a colourful language to describe its various components. Here’s a guide:

Local brew Indigenous alcoholic drinks made from traditional ingredients, like coconut toddy (from the sap of palm trees in Kerala and other parts of South India); feni, a Goan liquor made from distilled cashew fruits; mahua, a wine made from the flowers of a tropical tree, and chhaang, a barley beer drunk in Tibetan and Nepali communities, and popular in other parts of the Himalayas.

Country liquor Low-cost, mass-market alcohol distilled from molasses, then diluted with water and given fruity flavours like orange, lemon or others. Sold in small, state-level brands by registered, legitimate companies. Legal and taxed in many states, but banned in others.

Indian-made foreign liquor Spirits that are flavoured like western-style liquors, mainly whisky, vodka, brandy and rum. Often blended with imported whisky for flavour. Targeted to more upmarket consumers.

Hooch Unregulated, illegal alcohol, made using opaque production techniques and often adulterated with dangerous chemicals. Implicated in lethal drinking tragedies, especially in states where low-cost forms of more regulated alcohol, are not available, like Gujarat and, more recently, Bihar.

‘Spurious’ (counterfeit) alcohol Low-grade alcohol — either hooch or country liquor — masquerading as more costly Indian-made foreign spirits or upmarket imported brands. Spurious liquor rackets are run by criminal gangs, who use second-hand bottles of high-end liquor brands and fake labels.