Despite hundreds of attempts, only a select few beer brands have made the successful transition from local to global.

Kos Apostolatos, David Atkinson and Joseph Poore from management consultancy firm Marakon examine the successes and failures of global brand building in beer, market dynamics and best practices across the FMCG sector.

Freddy Heineken, the grandson of Heineken founder Gerard Heineken, started his career with the family company in 1942 and became Chairman of the Board in 1971. Freddy was an eccentric man and a noted salesman who fell in love with American advertising and marketing. He was extremely focused on consumers, very hands-on and rightly credited with the creation of the Heineken brand “personality.”

When Freddy became chairman of the Board, he pushed hard to expand Heineken beyond its local origins. Although Freddy had a dream to build a global beer brand, what people often don’t know is that he did not have any formal marketing education or detailed knowledge. His approach was primarily entrepreneurial and instinctive.

He did, however, understand that the Heineken brand had the potential to be unique among other beers and decided to put Heineken on the global map. His line of thinking was fivefold:

– Appeal to the young adult consumer

– Position the brand as premium and hip

– Create a green bottle with “export” on the label

– Craft a beer with superior and consistent taste

– Make it globally available

His experience in America helped him understand that a beer brand has to be unique to be successful globally. Freddy realised that in each market around the world there was a pocket of similar consumers that would drink Heineken, and he strove to reach them.

Although Freddy made the big difference in early days, his successors like Thony Ruys and Jean-Fran?ois van Boxmeer deserve credit for developing a leading export business model that ultimately took the brand to over 170 countries, generating 25 million hectolitres of sales volume and premium pricing in most markets.

Amazingly, all this happened in the absence of an experienced professional marketer in the lead until the 2010 recruitment of Alexis Nasard as chief commercial officer, who immediately made it his top priority to accelerate the brand’s growth and complete the “last mile” of the brand’s globalisation.

Under recent leadership, Heineken has re-entered Interbrand’s Top 100 global brands at 91, the third ranked beer behind only Budweiser (29) and Corona (86). It stands alongside Coca-Cola (1), Pepsi (22), Jack Daniels (78) and Smirnoff (89) as a truly great global brand, and Alexis aims to have the brand as equally recognised as Apple, Google and Nike.

Today more than 75% of beer sales are still on local brands in every major country, and international brand volume represents only 11% of the global total. Why have so few other beer brands been able to achieve the same long-term, global success as Heineken?

Having spent the last six months working to answer this question, Marakon will unveil the four secrets to building a successful global beer brand, together with analysis of the current state of the international beer market, in a series of articles over the coming weeks.

Despite remaining a highly localised product, the beer industry has seen dramatic consolidation over the last decade, with a significant impact on profitability.

Having examined the steps which led to Heineken’s successful positioning as one of the world’s few global brands, Kos Apostolatos, David Atkinson and Joseph Poore from management consultancy firm Marakon consider the impact of consolidation on the beer industry.

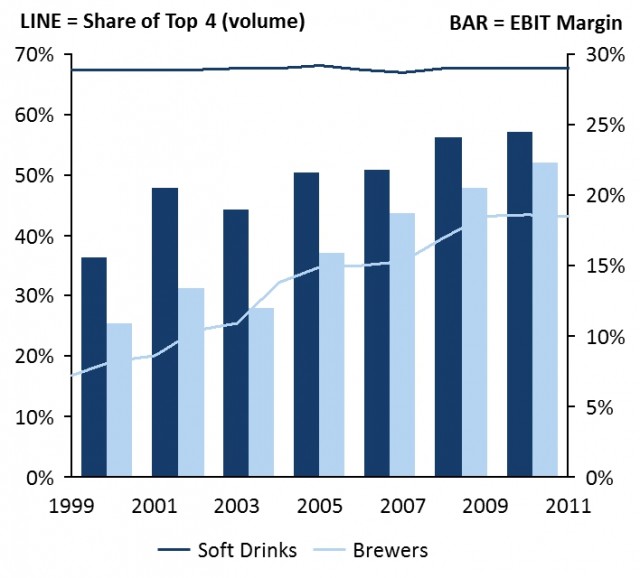

Figure 1: Share of top four companies and industry EBIT margin

Beer has been sold in similar form and taste for thousands of years. Local tastes, high transport costs, short shelf life, availability of ingredients and packaging, taxes on imported alcoholic products and impenetrable local wholesale networks have ensured beer remained a highly local product.

As the wave of industrialisation followed by globalisation swept change through the world, the beer business evolved but largely remained local.

On the other hand, consumer goods companies like Coca-Cola and Pepsi are different. Free from the constraints of historical taste preferences, legacy systems, laws and infrastructure, they have been able to innovate and change across areas such as outlets, channels, distribution and packaging. Using one key brand, they grew their business with a global mind-set from the start.

The beer industry has consolidated dramatically over the last decade. In 1999, Coca-Cola and Pepsi together controlled almost 70% of worldwide soft drinks sales, whereas the top four brewers generated only 17% of global beer sales. Beer was viewed as one of the least consolidated, and least profitable, industries in FMCG.

Today the top four brewers account for 45% of global volume and over 55% of global revenue. The profitability of the beer industry has doubled (see Figure 1) because of greater scale, multiplier effects of reduced competition and the profitability of emerging markets.

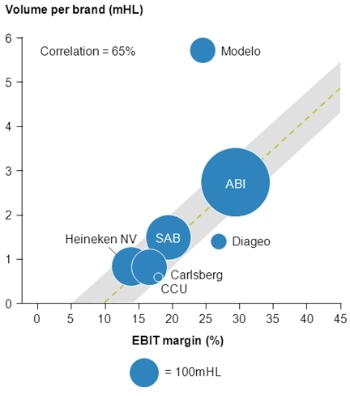

Figure 2: Correlation between scale and profitability

In local beer markets, brand consolidation is likely ?to continue. Beyond industry consolidation, brand consolidation brings further tangible and intangible benefits, including operational leverage, efficiency in advertising spend and increased consumer recognition. Companies with higher volume brands tend to be more profitable (see Figure 2).

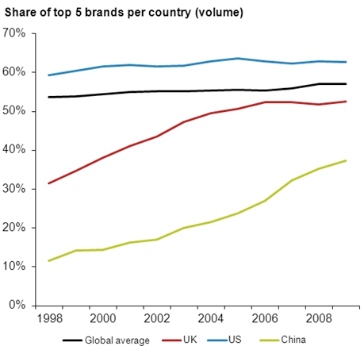

Brand concentration is slowly starting to occur across both developed and developing countries (see Figure 3). For example, the top five brands in China now represent 37% of the market, up from 12% 10 years ago.

In the key African markets of Nigeria and South Africa, Star and Castel are leading the way, growing share at the same time as the growing market becomes more profitable.

These trends toward both industry and local brand consolidation in beer, and historical trends across other FMCG industries, indicate the future is set up for continued attempts to develop global beer brands.

Figure 3: Increasing share of the top five brands in local markets

Having highlighted increasing levels of consolidation within the beer industry and the benefits of such a shift, Kos Apostolatos, David Atkinson and Joseph Poore from management consultancy firm Marakon, explore how to go about building a global beer brand.

Doing so is not obvious and requires a systematic approach and patience in your long-term investment. We have defined four key steps for getting there:

Step 1: Define the benefits of global brands to your organisation

In our discussions with leading brewers, we found inconsistencies within and across organisations about the benefits global brands bring. Based on our experience they are:

Leverage international media and advertising platforms: Only a global brand like Budweiser can take advantage of being the face of the FIFA World Cup.

Better route to market: Premium international imports like Heineken and Corona are musts in the on-trade and off-trade.

Consumer confidence: Being international makes you more credible; e.g., as Beck’s has expanded its footprint, it has also boosted awareness and credibility.

Economies of scale: AB InBev and Heineken are saving 50% or more by producing one high-quality Total Variable Cost (TVC) instead of different TVCs for multiple markets.

Repeatable and scalable model: Corona has expertly created a repeatable export model that takes into account each stage of a brand’s lifecycle in a country, so subsequent launches are increasingly effective.

Exercise 1:Define the benefits of global brands to your organisation.Take the list above as a starting point and assess:

The benefits of global brands to your organisation

The implications of moving toward a global brand-led strategy

The timelines for your project

We identified the top 10 global beer brands as indicated both by the revenue, volume generated across multiple markets and the intent to be global (i.e., advertisement on global media platforms).

Top 10 global beer brands

Countries ?with total?revenue?> €50m | Countries ?with volume ?> 100thHL | Advertise on ?global media ?platforms | |

|

|

| |

| Heineken | 32 | 37 | ? |

| Carlsberg | 22 | 23 | ? |

| Corona | 13 | 9 | ? |

| Guinness | 12 | 15 | ? |

| Budweiser | 11 | 13 | ? |

| Stella Artois | 11 | 11 | ? |

| Beck’s | 9 | 6 | ? |

| Miller ?Genuine Draft | 9 | 9 | ? |

| Amstel | 7 | 9 | ? |

| Foster’s | 5 | 4 | ? |

Defining what a global brand means to your organisation is the first step toward success. It helps you set the governing objective for the brand, communicate the benefits of the brand internally and break down the “local prejudice” barrier that is still prevalent in the beer industry today.

As we analysed hundreds of beer brands, it was striking to see that for those that had made the transition from local to global, there was no common reason for their success.

What unites the eight global beer brands is that they have a unique customer value proposition to the customer and/or have an advantaged business model.

Through our research we consistently heard that to build a global brand you need great taste, local image and a brand that is currently profitable. We believe these factors were, and remain, critical to building a local but not global beer brand.

Being very good in a number of areas is not enough to give a brand the front running in the global market. The starting point for selecting the right brand to take global is a unique customer value proposition.

Uniqueness means that there is a place in the mind of the consumers where your brand sits alone with clearly identified consumer “benefits”, ultimately driving strong buying behaviour and loyalty.

Why are taste and profitability not as important as a unique customer proposition?

Consumers are embarrassingly poor at differentiating between lagers in blind taste tests. A Carling study found consumers could not identify a significant difference in taste across five of its competitor’s lagers nor could they identify their favourite brand as having superior taste.

Once labelled, the consumers immediately ranked their preferred brand as superior across taste factors. Taste, to a large degree, is all in the eyes rather than the palate.

We also heard brewers should choose which brand to take global based on how profitable the brand currently is in key countries (with the idea being that if you are successful locally, you have a better chance of becoming successful globally).

We believe that this will lead to the wrong brand being promoted on many occasions as profitability is a not a leading but a lagging indicator of the overall success of a brand.

Global brands—uniqueness and value to their owners

Estimated revenue to brewer (€m, 2011) | Share of group ?revenue (%, 2011) | ||

| Top 10 global beer brands | |||

| Heineken | Footprint and international image | 4,800 | 28% |

| Budweiser | Scale and resulting A&P spend | 5,300 | 18% |

| Corona | Packaging and experience | 3,300 | 72% |

| Carlsberg | Mainstream price point and image | 1,950 | 23% |

| Guinness | Irish stout | 1,050 | 8% |

| Stella Artois | Sophisticated European image | 1,300 | 4% |

| Beck’s | Affordable premium proposition | 1,300 | 4% |

| Miller Draft | “American-ness” | 1,000 | 8% |

| Amstel | Heritage pilsner proposition | 1,100 | 6% |

| Foster’s | Global license and positioning | 1,200 | n/a |

| Brands with potential to enter the top 10 | |||

| Tiger | Definitive Asian beer, youth focus | 250 | 12% |

| Peroni | Focus on cities and niche markets | 250–400 | 2%–3% |

| Desperados | Unique RTM and taste profile | 150 | 1% |

| Kirin | Packaging and image | 3,800 | 62% |

| Asahi | Packaging and image | 5,300 | 43% |

| Brahma | Packaging and image | 3,400 | 11% |

| Kingfisher | Pride of India, professional focus | 450 | 79% |

| Snow | Scale and resulting A&P spend | 1,950 | 90% |

| Blue Moon | Craft beer at scale | 150 | 6% |

We discovered that brands that fail to identify (and sustain over time) a material point of uniqueness on the global consumer map will fall into a negative cycle, slowly reducing volume and profitability in all markets over time. Unique brands are able to leverage their strengths to increase consumer appeal and grow rapidly.

Having stressed the importance of creating – and sustaining – a sense of uniqueness for the global consumer, Kos Apostolatos, David Atkinson and Joseph Poore from management consultancy firm Marakon, compare two brands who got this right and wrong.

It is not enough to have a unique customer value proposition. A truly global brand also requires a business model that supports the brands uniqueness to reach its customers (e.g., privileged route to market, unique ability to engage new media, superior brewing scale).

Fifteen years ago, Foster’s looked like it would take the beer world by storm. It had secured global licence arrangements, had a one-of-a-kind advertising campaign and tapped into the laid-back Australian culture of beach, barbecue and watching TV with mates.

Volume has been steadily declining since 2005, including falling by 50% in the US (which it set out as a “priority market”).

What went wrong?

We believe that Foster’s suffered from confused positioning and lack of success in its home market.

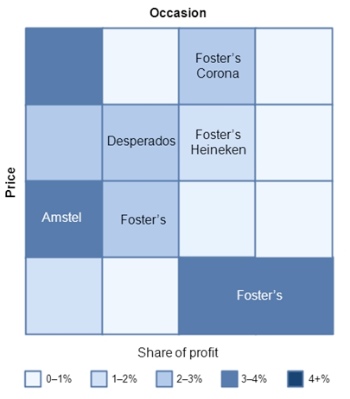

In the last decade, Foster’s has gone through multiple re-brandings, positioned itself across every price segment (from discount in Ireland and Australia to super-premium in Portugal and Italy) and has used varied RTMs from JVs, distributor agreements and its own operators, all of which had different priorities for the brand.

Foster’s failed to drive success in Australia, meaning low visibility to tourists and no core to draw on to cross-subsidise A&P spend. SABMiller now has an opportunity to change all this.

At the core of the revitalisation effort is to re-establish the core of the customer value proposition the brand lost and fundamentally rethink the business model.

The comparison with Corona is instructive. Corona sits at the other end of the spectrum with a growing 1.5% of global beer market volume (#4 brand globally).

In 2011, the brand generated ~€0.5bn of EBIT, almost half of Modelo’s total at a 25% EBIT margin, a level of profitability on par with the soft drink giants.

It has consistent pricing (upper-premium or lower super-premium), very few SKUs, a consistent and clearly differentiated pack type, special consumption style (with lime) and “Mexican-ness.”

Unlike Foster’s, Corona is very strong and profitable in its home market and has one clear global RTM through its leading export team.

What went right?

Corona built a unique export business model based on its customer proposition. Outside Mexico and the US, Modelo participates in small, specific and highly profitable on-trade segments where it controls a niche position.

The result has been small but sustainably strong and profitable market shares in over 30 global markets and throughout Modelo has stayed true to the core strengths of the brand’s business model to drive profitable growth.

Exercise 2: Identify the unique customer proposition and right business model to support it.Develop a short-list of your brands with the potential to become global.Build a matrix listing key characteristics (e.g., positioning, image, packaging) and assess whether they have the potential of a unique proposition.

Build a global consumer map with major needs-based segments on it.

Position your selected brands onto the consumer map.

Assess the overlap and prioritise those brands you believe have the greatest potential (i.e., “accessible headroom for profitable growth”).

Place the competitor brands you believe have a global footprint or unique value proposition onto the map (these can be other beverage brands).

Assess the gaps and overlap; what is the unique position for your brands?

Select the brand with the right proposition and the least competition.

Consider the business model that will allow you to reach the right occasion or right consumer type (i.e. distributor model choice, outlet choice, sales team) and your desired price (i.e. through marketing mix, efficient supply chain, production agreements).