Citrusy, light-bodied with a hint of sweet. That’s Beteljuice for you, a beer infused with paan and lemongrass. For those who like to venture on the dark side, there’s the roasty Kaapi stout, which marries malt with coffee beans.

To revisit fond childhood memories, try the mango beer created with Alphonsos sourced from the farms of Ratnagiri in Maharashtra.

Craft beers, small, independent and traditionally brewed, have become a phenomenon that has captured the imagination of beer connoisseurs and brewers in India. Brewmasters, microbreweries and brewpubs, working independently or in collaboration, are creating signature brews with local flavours and ingredients. That’s akin to offering gourmet cuisine to the average Indian beer enthusiast who is used to drinking from mass-produced bottles or draughts.

Craft beer lends itself to experimentation because it is produced in limited quantities by house experts and the ingredients can be easily substituted or improvised with additives or adjuncts like fresh fruit or herbs. Added to this is the quick turnaround time of two weeks to one month for a brew to ferment and take flavours.

Craft beer lends itself to experimentation because it is produced in limited quantities by house experts and the ingredients can be easily substituted or improvised with additives or adjuncts like fresh fruit or herbs. Added to this is the quick turnaround time of two weeks to one month for a brew to ferment and take flavours.

As beer consultant John Eapen says, “If a small sample or batch doesn’t work out, it’s easier to move on to the next recipe in a craft beer versus a wine or a whisky that takes much longer to ferment and form.”

Arbor Brewing Company India in Bengaluru, a city hailed as the nation’s beer capital, experimented recently with a lemongrass betel leaf brew called Beteljuice that sold out in three weeks. The initial recipe for the lemongrass, paan-infused ale came from Karthik Singh and Vivek Maru, cofounders of Bangalore Brew Crew, a community of craft beer enthusiasts. They approached Arbor’s head brewers to prepare the light-bodied ale for a full batch at 1,000 litres.

It was a huge success and the brewpub now wants to create more distinct Indian flavoured brews at least once a month. “For such a new market we have been very pleased with the response,” says Logan Schaedig, head brewer at Arbor.

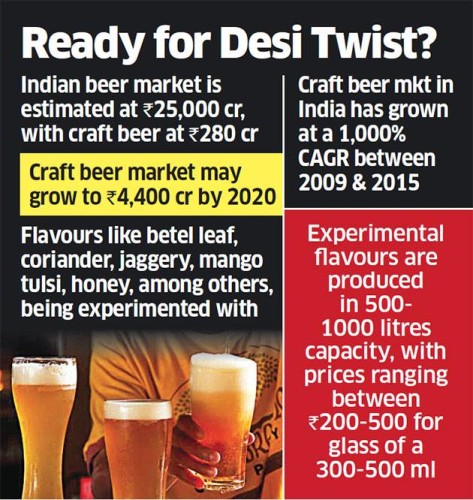

The rise of India’s craft beer market has been phenomenal, growing at 1,000% annually between 2009 and 2015, according to Mumbai-based craft brewery Gateway Brewing Co.

The growth is most evident in Bengaluru, Mumbai, Pune and Gurugram (formerly Gurgaon), which have more than 60 brewpubs among them. And with the craft beer market projected to expand to Rs 4,400 crore by 2020 from about Rs 280 crore now, the zeal to capture the consumer’s imagination with Indian-flavoured experiments comes as little surprise.

The size of the overall Indian beer market is estimated at Rs 25,000 crore. Gateway Brewing has been experimenting with Indian flavours for some time.

Last year, it released Summersault, a pale ale for which Gateway used coriander, for aroma, over hops, a staple in Belgianstyle wheat beers. The result, says founder Navin Mittal, was spectacular.

Gateway followed that up with Kaapi, infused with coffee beans, and a Darjeeling black tea and Earl Grey beer that it brewed for the restaurant The Bombay Canteen, where it was served with Khaari biscuits, a salty cracker biscuit.

“Times are changing for Indian consumers. They are now well-placed to receive experimental brews given the growth in economy, urbanisation, and an aspirational population with disposable incomes,” says Mittal.

However, not every experiment works as the key lies in striking a harmony of flavours. For example, the Star Anise black pepper beer and the Double IPA brewed with beets at Arbor didn’t fly off the shelves.

“While experimentation is great, it’s a trial-and-error method to know what works,” says Shailendra Bist, cofounder at Independence Brewing Co., in Pune. Case in point being that while their collaboration beer Puneri Honey Basil Ale was a great hit, experimental batches with mahua, kokam and khas have not worked. Ingredients like garam masala or bhut jolokia chillies, too, don’t make sense for craft beer, he said.

In 2012, SABMiller India launched Indus Pride, a specialty beer with four flavours — Citrusy Coriander, Citrusy Cardamom, Spicy Fennel and Fiery Cinnamon. The company pulled it out of the market three years later owing to a lack of commercial scalability and lukewarm response that pointed to the market not being ready then for localised flavours.

The beer consultant Eapen says that’s a thing of the past. People are well-travelled now and exposed to various experimental flavours. Besides, the booming food and beverage industry that’s always on the lookout for the next new thing has contributed to the change, he said.

Darioush Afzali, director-marketing at SABMiller, is more optimistic for the company now. “Looking at how the tastes of Indian consumers are evolving, going forward there will be elaborate options across industrial and craft beer segments available to them,” he says.